“Information presented at the right time and in the right places can potentially be very powerful. It can affect the general social fabric.”

-Hans Haacke

What is activist art? The critic and activist Lucy R. Lippard describes activist art as a practice whereby "...some element of the art takes place in the "outside world," including some teaching and media practice as well as community and labor organizing, public political work, and organizing within artist's community."

The beginning of activist art is certainly debatable, but many date it to the ideological goals of the Russian Constructivist movement of the early 20th century. The Constructivists urged for a break with the aesthetic representation of the past and therefore the authoritative ideology of the previous era. They devised a secular anti-stylistic art to express the ‘temporary and transient’ nature of the times. An art was introduced that for the first time used agitation and activism to directly influence the people's consciousness and living conditions. (i)

There may be no clear universal understanding of the social benefits of art although many have tried to quantify it beyond its intrinsic value. (ii) Despite the widely held belief that art can play an important role in breaking down cultural taboos, political oppression, or unfair government practice, there is no way of gauging its true impact on social change. As Masahiro Ushiroshoji, a prominent organizer for the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum is quoted saying, “It is no longer possible to believe naively that art is all that is needed for achieving an understanding of other cultures and values or to heal rifts between societies and people.” (iii) Despite what might be perceived as a limitation, the fine arts are an invaluable means of communication because of the personal and subjective impact that the ‘felt experience’ can have on the viewer and more optimistically on society. Bernhard Heisig, a German painter whose work was exhibited in the USA the year the Berlin Wall came down, stated about his role as artist, “You cannot prevent war with art, but I can make a drawing of a hand, which will make everyone feel that this hand must not be destroyed.”

Activist art comes in all shapes and sizes. A few examples, which are in no way exhaustive, are community-oriented art (or art created with the community in mind), public art or ‘street art’ (that which is displayed in the public sphere and that therefore reaches potentially unengaged or unwilling audiences), art that is overtly political in subject matter, and art that utilizes conceptual tools and alternative mediums (posters, pamphlets, community action, etc.). Activist art typically responds to specific political problems, be it war and violence, the established social order and consumerist mentality, ethnic and gender identity, and the environment, and in turn seeks to create a new or increased awareness for its viewer. Another determining factor in the output of activist art is the political and national context in which the art is made. Countries with relative freedom of expression can push the envelope, but those who are faced with governmental or social control of creative expression must find other methods to achieve activism.

Banksy, a prominent UK graffiti artist, engages in critique through his site-specific art. Dove is a mural painted on the West Bank wall of Bethlehem. Banksy often employs obvious and direct imagery, in this case a peace dove wearing a bullet-proof vest, which he places within a very sensitive and public space. By making such juxtopositions, he forces the viewer to face what he perceives to be a contradiction or a social taboo. Because of the publicity and anger that his works attract (his works are often deemed illegal), Banksy’s identity has been kept a secret. Banksy is among an emerging set of international artists who use ‘street art’ as a means of public expression for activist agendas. Although his citizenship is in the UK, his daring escapades to reach out directly to the people in countries with more oppressive notions of freedom of expression often put him in danger of reprisal.

Banksy, Dove Mural, West Bank, 200

Overt political critique can also be found in the work of Fernando Botero, a veteran Colombian neo-figurative artist. Botero found little encouragement from US arts institutions in 2005 when he began his visual renderings of Abu Ghraib prison scenes. His subject matter is typically political and activist, as was his 1971 painting Official Portrait of the Military Junta, which depicts those in power in Colombia as overgrown, dangerous children. (iv) His paintings of Abu Ghraib are graphic and unsettling, which is just the effect he is going for. He was so disturbed by the written reports of human rights conditions in the prison that he was compelled to represent them visually, with the hope that the artworks’ power to affect the consciousness of the viewer would leave a lasting impression.

Fernando Botero, Abu Ghraib, 2005

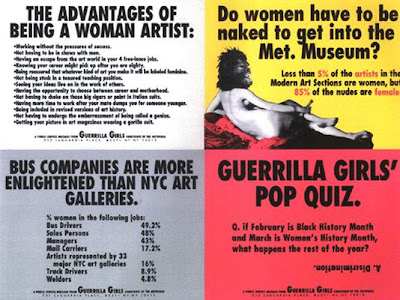

The Guerilla Girls, like Banksy, work anonymously to create a clever form of activist art. The Guerilla Girls are the self-described conscience of the art world; criticizing the powerful arts institutions, galleries, and art critics by plastering posters and handing out flyers that inform arts admirers and anyone who will look of the statistically proven discrimination of women and minorities that exists within the arts institutions. Their goal is to stop the patriarchal and racist ideology that is being perpetuated in the arts discourse.

Guerilla Girls, Activist Posters

Art for social change is the modus operandi for Wochenklausur, a German artist group created in 1993 that develops concrete proposals aimed at small, but nevertheless effective improvements to socio-political deficiencies. They no longer see art as a formal act but as a means for an intervention into society. They believe that, “art should deal with reality, grapple with political circumstances, and work out proposals for improving human coexistence” and that, “art has political capital at its disposal that should not be underestimated. The use of this potential to manipulate social circumstances is a practice of art just as valid as the manipulation of traditional materials.” (v) For one of their past projects, they created a system to recycle used theatre and exhibition sets to make furniture for those of the community in need.

A different approach is taken by Paul Chan, a Chinese artist and activist living in NY, who garnered much attention when he collaborated with the collective Friends of William Blake to produce The People's Guide to the Republican National Convention (2004), a free foldout map detailing everything a protester needed to get in or out of the way during the RNC in New York. In a recent interview, Chan asserts that he separates social activism from art; the former, he believes, attempts to act upon daily reality while the latter sees to transcend or re-imagine it. (vi)

Although Chan sees himself as divorcing art from politics and vice versa, it is quite apparent in his art that the two influence each other greatly. Chan in a previous politically charged endeavor worked with Voices in the Wilderness on their campaign against the war (and now occupation) in Iraq. He is continually influenced by world affairs, injustice, suffering and survival and in turn how they can be expressed visually to potentially affect social change.

Paul Chan The People's Guide to the Republican National Convention (2004)

So, where is the activist art in Sri Lanka? In 1998, there were several public art works whose activism was anti-war or rather the promotion of peace in scope. (vii) Yet, there has been very little by way of public activist art since. It became apparent to me that activist art is happening quietly or ‘under the radar’ in Sri Lanka. In speaking with local artists, the manifold challenges and frustrations and subsequent solutions that fine artists are devising to face the problems of war and censorship made their presence known.

In response to a question regarding the state of public activist art, artist and art historian Jagath Weerasinghe states that, “[Sri Lankan] artists in general are a bit frustrated with the whole setup. You know that ours is a highly polarized society, it is polarized in terms of political parties, caste, regions and religions. I know this is not unique to Sri Lanka, but here the situation is so acute and pathetic. In a situation like this public art doesn't make much sense. In other words, in a context where there are no citizens, how can public art gather any meaning? As such, I personally believe working from the margins within selected environments planting your ideas so that they will gather momentum in the long run.” (viii)

One such example of this kind of community focused program is called 'In Our Village', an activist project created by Theertha Artists’ Collective where school children from a few selected villages produce a cultural map of their village and explore critically their respective villages in terms of history and culture. The goal is to revitalize lost craft systems and increase understanding of the multi-cultural heritage of Sri Lankan society.

Another similar endeavor by Theertha is their programming dedicated to fostering the creativity and community participation of women artists. These workshops and colloquium encourage female artists to work critically, rather than only making art for art’s sake. The programs encourage participation and idea sharing, as well as provide a forum to critique their role as women and to explore a feminist approach to art making.

Sri Lankan artists such as Sujeewa Kumari and Anoli Perera are actively questioning women’s traditional roles and in turn national identity politics through the medium of performance, photography, installation and sculpture. According to Anoli Perera, being a woman artist “is tough... tough because of the social expectations and restrictions imposed on the woman's general conduct and behavior.” In her estimation, art discourse is inherently patriarchal; assuming the role of woman artist often contradicts the general expectations that Sri Lankan society imposes on women. (ix)

Anoli Perera, Dinner for Six courtesy of Theertha Digital Art Archive

A good and recent example of local arts initiative is Kooii Arts Foundation. The foundation is set up to act as an intermediary between Sri Lankan artists and a global audience with the hope that new linkages will inspire discussion and increased cooperation. Kooii’s first exhibition, postcART, included artwork by 25 Sri Lankan artists and was held in Galle during the Literary Festival in 2008.

Artists such as Bandu Manamperi, T.G.P. Amarajeewa, Sanath Kalubadana and Pala Potupitiya make overt political critique about war and violence, and the soldier through the image of government soldier. In Sanath Kalubadana’s 2007 exhibition ‘Love that Can’t be Expressed: The War, The Soldiers, and the Memories of Everyday Life’, he uses sculpture to express the soldier’s ‘journey of aimless reality’. According to Jagath Weerasinghe, the work of these four artists have, “given rise to an important and an exciting body of work that reflects the anxieties of a nation caught in a bloody war for over two decades.” (x)

Sanath Kalubadana, Untitled, Fiber, 2007, Life sized. Courtesy of Theertha Digital Art Archive.

Although the fine arts in Sri Lanka often garners less attention from government and the community-at-large than more familiar forms of artistic dissent such as theatre and cinema, the fine arts still fall prey to censorship. For instance, the Ministry of Cultural Affairs, when it gives the National Gallery of Art to individual artists, asks that the artists do not show anything that is ‘detrimental to Sri Lankan culture’. According to Jagath Weerasinghe, artists are often left lost because one does not know what constitutes Sri Lankan culture. For many, an artist’s role is to question concepts of culture and narrative; this leaves the Sri Lankan artist in quite a bind. Self-censorship is thus required of the artist who then must undermine their own critique and freedom of expression to uphold an idea to which they may not prescribe.

Overall, the obstacles to arts for social change in Sri Lanka are government-mandated censorship, self-censorship, lack of funding, and lack of community awareness, etc. But, what can be done? There are no easy answers. Many of the artists and programs mentioned are making important strides. Perhaps the first step is creating an even more cohesive arts community. This could be done through monthly meetings of artists who may not already be working under the same ideological framework or to create online forums in which ideas can be shared. Another suggestion is to implement more programs like Theertha’s ‘In Our Village’, which encourage community participation. The third perhaps is to increase the conceptual and critical components of art practice in Sri Lanka. According to art critic Arthur C. Danto, the real power of art can often be found in the censor’s deeming it dangerous. (xi) Art can use signs, codes, and concepts not easily read by those on the periphery and can be an important communicative tool for dissent.

----------

i) http://www.wochenklausur.at/texte/kunst_en.html

ii) a good reference here is Gifs of the Muse: Reframing the Debate About the Benefits of the Arts, published by The Wallace Foundation, http://www.wallacefoundation.org"

iii) Turner, Caroline. Art and Social Change: Contemporary Art in Asia and the Pacific (2005), p. 5. Pandanus Books.

iv) “Botero’s Political History”, ArtForum Magazine by Jennifer Allen 04.18.05

v) http://www.wochenklausur.at

vi) Paul Chan: Art in Reverse, Rachel Kent. ARTASIAPACIFIC, No. 56, Nov/Dec 2007

vii) In 1998 there were two sets of public art work. Information can be found in which are outlined in ‘The Performance of Hybridity in the Visual Culture of the No Order Group of Sri Lanka’ by Yolanda Foster. The Hybrid Island, 2003, ed. Neluka Silva. Social Scientists’ Association 2004.

viii) Excerpt taken from email interview

ix) Excerpts taken from email interview

x) From introduction to catalogue ‘The Art of Sanath Kalubadana: Love that can’t be expressed: The war, the soldiers and the memories in everyday life.’ 2007, Theertha International Artists Collective.

xi) Danto, Arthur C., ‘Dangerous Art’, Beyond the Brillo Box, University of California Press, 1998.

About the author: Lindsay Aveilhe is a curator, photographer, and writer who currently lives in Colombo, Sri Lanka. A native of Oklahoma, she has worked for the Committee for the Discrimination Against Women at the United Nations, New York City, and as a freelance photo editor.

1 comment:

.... nice

Post a Comment